- Cambio de Juego (In English)

- Posts

- Up-back 3rd player combos- The key to escaping pressure?

Up-back 3rd player combos- The key to escaping pressure?

Studying press escaping, and why it matters for some teams

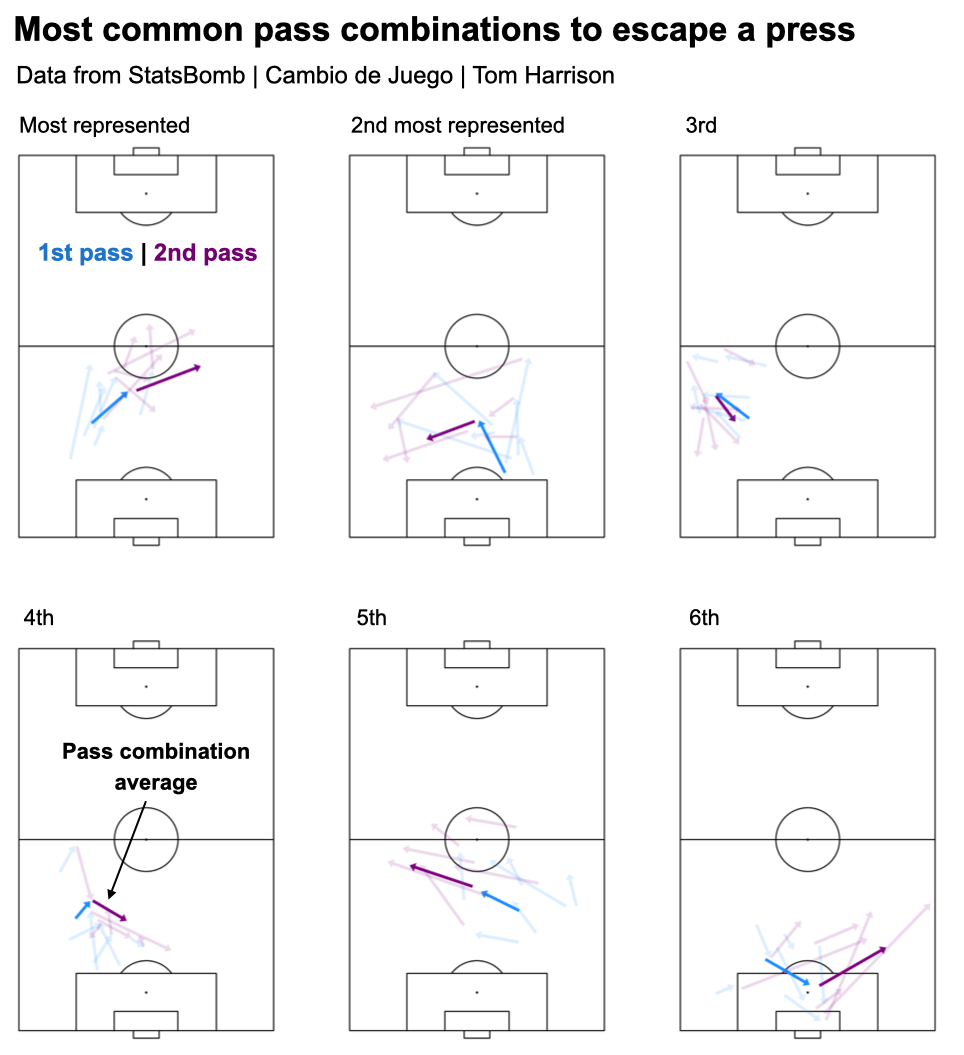

Photo from The Guardian, data from StatsBomb

Summary:

Escaping a press increases ball retention, and stronger teams tend to escape a press more frequently

Diagonal circulation and third player combinations are most commonly used to find a free player, with the up-back combo particularly efficient at escaping pressure

It’s most difficult to escape pressure on the wings, and in the defensive penalty area

A press-escaping metric would be a valuable addition to analysis of retention under pressure, high retention is less useful if the majority of passes lead to another teammate being put under pressure

Recently, I’ve been exploring some of the finer details of pressing. Using StatsBomb open data; I’ve displayed the importance of rhythm, and limiting opposition time on the ball in a high press, and I’ve developed metrics and visualizations to study pressing triggers and orientation.

In this article, I’m switching the focus. By analyzing the side under pressure, I’ll assess the concept of “escaping” a press, and finding an open teammate.

Defining the situations to analyze

Without tracking data, it’s difficult to accurately define when a team is facing a collective, coordinated press, rather than just one player jumping on their own. Avoiding these events was important, as finding a free teammate isn’t difficult when the pressing player is disconnected from the defensive block.

Therefore, I filtered for situations where two consecutive ball carriers were pressurized, inside their own half.

Disclaimer: Most of StatsBomb’s open data isn’t too up-to-date and a more current study could create different results. Changes in play styles and the goal kick rule has led to more teams building-up with short passes (at least, until this Premier League season), whilst there’s been an increasing focus on player-oriented pressing in elite football.

Analyze the next action

After isolating consecutively pressurized ball carriers, I looked at the following action. To simplify the analysis, I defined three possibilities:

Lose the ball

Make a pass to another player under pressure (in the three seconds after receiving)

Escape the pressure (a pass to an open player, or winning a foul)

Some notes on the definitions:

I removed passes to a teammate under pressure, following ball progression. Without tracking data, it’s difficult to define whether or not these situations count as escaping a press. The team is still under pressure, but the ball progression may have broken a line of opposition press. There weren’t too many of these situations in the data set, and therefore I believed it was best to remove them from the analysis, rather than creating another category.

I also haven’t considered passes to the goalkeeper for the “escape the pressure” category. Returning to the keeper can be seen as re-starting the possession, and when studying pressing triggers, I found that jumping to a keeper leads to more opposition ball progression than any other position. Therefore, it may be an advantage for a team to attract pressure to their keeper, which can lead to an outfielder becoming unmarked, rather than using them as an escape valve.

A key concept if a team values ball retention

Escaping a press, rather than finding another teammate under pressure, greatly reduces the possibility that the in-possession side will lose the ball in the following 6 seconds. There’s also a slight impact on xG difference in the next 20 seconds.

% ball losses in the next 6 seconds | xG difference in the next 20 seconds | |

|---|---|---|

Escape the pressure | 8.9% | +0.01 |

Pass towards pressure | 38.1% | 0 |

Many of the strongest teams during 2015-16 were more effective at escaping a press, and maintaining possession following pressing actions on consecutive ball carriers. As expected, sides known for their high possession style stand-out the most; Barcelona, PSG and Napoli under Maurizio Sarri.

However, there are examples of teams with a strong xG difference without showing high efficiency under pressure, particularly in the Premier League. It was a strange, and weak, season in England. Leicester City shocked to win the title, Manchester City were the only English side to get past the last-16 of the Champions League, and the national team were knocked-out of Euro 2016 by Iceland. Everton, under Roberto Martínez, were the most effective Premier League side at escaping a press.

The following season turned out to be a watershed moment for English football and tactical styles. In the short term, Antonio Conte popularized the back-three on the way to winning the 2016-17 title with Chelsea, whilst the arrival of Pep Guardiola, and his rivalry with Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool, led to long-term tactical changes. It seems that tactical development was required to catch-up with the rest of Europe.

The passing combinations used to escape a press

Apart from having players that can win fouls consistently, or create space with their 1vs1 abilities, I wanted to analyze methods that teams use to escape pressure.

I focused on two-pass combinations. The first pass was played between the two players that were put under pressure, with the second pass finding the free player. I filtered out longer carries and dribbles which can greatly change the game situation.

To identify similar combinations, I used a clustering method, and then filtered for those that more frequently escape pressure.

Some combinations are similar, but reversed. The most represented cluster, and the 5th most, show two passes towards the same direction, which are normally diagonal. These passes move the ball from one half-space to another, and often require a player to open their body and let the ball run across them.

For example, Jude Bellingham uses his body shape here to trick the pressing defender, attracting his opponent towards his left side.

At the last second, Bellingham shifts his hips and lets the ball run across him. As the defender has committed to pressing from the other side, Jude creates enough time and space to switch the ball to the right side of the pitch.

Many midfielders are more effective at this technique when receiving from a certain side, even a great pivot like Sergio Busquets.

John Muller wrote more about this concept in his “How Football Works” series on The Athletic:

The 2nd and 4th most represented are methods of finding the “3rd player”. This is particularly effective when an opponent orients their press to block a sideways passing lane, and tries to force the opponent to play towards one side of the pitch.

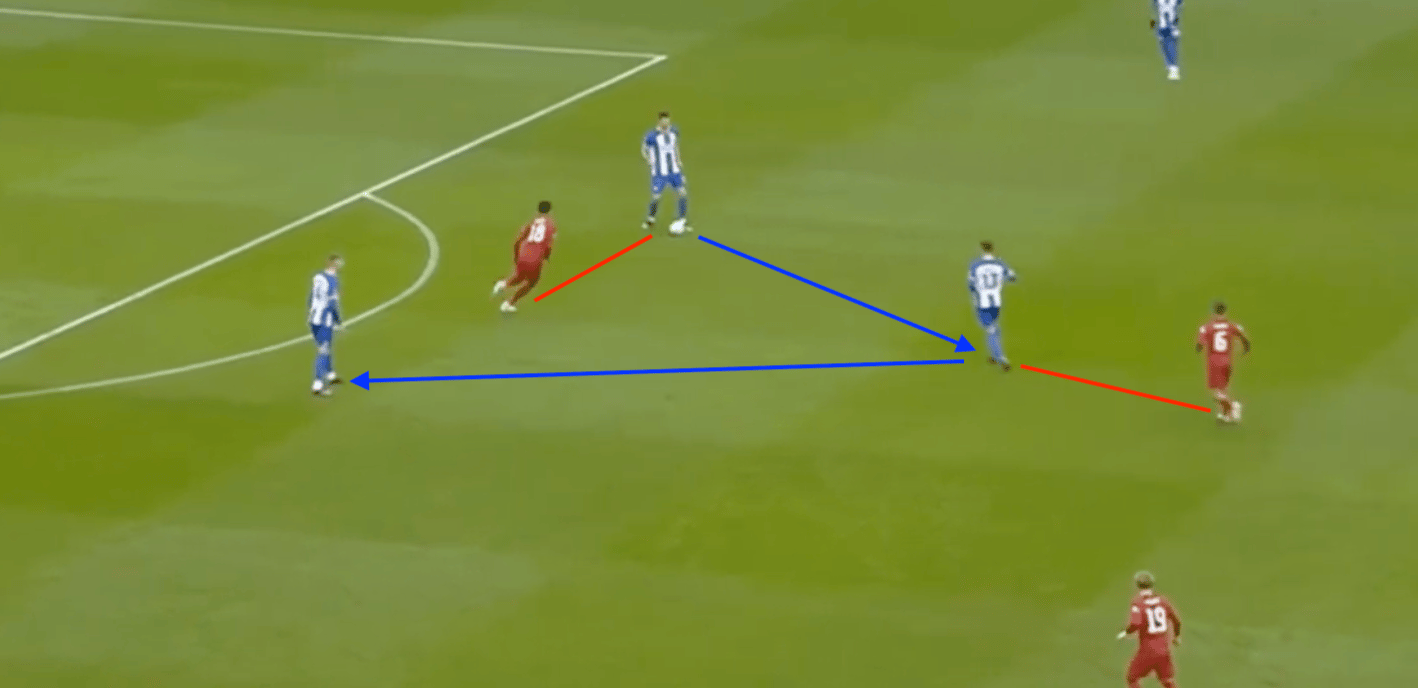

For example, Liverpool press Brighton’s two center-backs with one player, cutting the passing lane between the two of them. Therefore, Brighton use a pivot player to find the other center-back.

Brighton escape the pressure with this combination, and the center-back has time to carry the ball forwards and pick-out the best available pass. Even before Roberto De Zerbi had coached a first division side, this was a common combination used to escape pressure.

The 3rd cluster also shows a forwards first pass and backwards second pass, but in this case the ball remains on the left wing. Finally, the 6th cluster is simple ball circulation from the left to the right, likely using a goalkeeper, center-back or pivot midfield in the middle of a back-three, which can overload the first line of pressure.

Up-back combinations most frequently escape pressure

By defining various passing combos, some of which came out in the cluster analysis, we can assess which pair of passes most frequently escape a press. Again, the two passes in the combo were made by players that were put under pressure. The efficiency % assesses the % of passes that found a teammate in space (without pressure).

Combination | Description | Press escaping efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|

3rd player (up-back) | Forwards pass followed by backwards pass to a 3rd player | 53% |

Switch | Short pass followed by a switch of play | 44% |

Circulation | Two sideways passes, played towards the same side of the pitch, neither are switches | 41% |

3rd player (sideways) | Forwards pass followed by a sideways pass to a 3rd player | 40% |

Wall (backwards) | Forwards pass followed by a backwards pass to the same player | 38% |

Open body shape | Two forward, diagonal passes, to a 3rd player | 33% |

Wall (forwards) | Forwards pass followed by a forwards pass to the same player | 32% |

Up-back 3rd player combos are even more efficient that switches of play, which are often encouraged to move the ball into space, but can be difficult to produce with accuracy, particularly under pressure.

Whilst the “open body shape” combo is often used to escape a press, two-thirds of the time it leads to the in-possession team remaining under pressure. Not too surprising given that both passes are played forwards.

It’s easier to escape central pressure

As found in previous studies, pressing actions are more effective out wide, as the sideline acts as another defender. The heat maps show a lower rate of losses after central ball receptions, focusing on where second pressurized player received, and more passes to space.

The center of the pitch is valuable in build-up, but teams require players with the abilities to scan and orient their body effectively in order to deal with 360 degrees of options, and potential pressure, plus a structure that facilitates up-back combos when required. Whilst there’s a lower chance of losing the ball centrally, transitions that begin in the center tend to lead to more dangerous opportunities.

A metric to analyze players?

Well, it passes the Messi test.

Top five players at escaping pressure (own half) in Europe’s “big five” leagues during 2015-16

Player | % Escape | % Ball loss |

|---|---|---|

Thiago Motta | 74% | 0% |

Maxime Gonalons | 71% | 8% |

Corentin Tolisso | 59% | 21% |

Arturo Vidal | 58% | 18% |

Lionel Messi | 57% | 15% |

Apart from Messi, it’s unsurprising to see central midfielders show up well in this metric. It could be adjusted depending on specific team play styles and expectations, but it seems a useful metric to be used alongside a player’s pass success under pressure. High ball retention under pressure is less useful if the majority of the passes lead to another teammate being pressurized, given the higher chance of a turnover later in the possession sequence.

An additional detail for pre-game analysis

Bringing together different parts of the article, I created a dashboard to analyze a specific team in these situations.

Sevilla in 2015-16 is a particularly interesting team to analyze given their high rate of escaping the press, but frequent ball losses. Sevilla were particularly effective from within their box, and when moving inside from the right wing. Forcing them deep on the left side or to progress centrally may have led to more ball recoveries.

Thank you for reading, if you’d like to contact me regarding any questions, comments or to consult my services, you can contact me on:

Linkedin - https://www.linkedin.com/in/thomas-harrison-a682a2175/

Twitter/X - https://x.com/tomh_36

También, se puede leer este artículo en Español- https://cambiodejuego.beehiiv.com/